How many know just how many upper and lower case letters children should be able to identify by the time they enter Kindergarten? How many are challenged to justify whether or not a child’s development and learning is considered typical or on track? Or confronted with the pressure to show growth for every child across key indicators.

Despite what some policy makers and publishing companies profess, predicting the age at which children will begin to perform or master various skills, is a nearly impossible task.

In other words, don’t panic, you aren’t alone. It is nearly impossible to answer questions such as:

- Is a child’s development delayed if they aren’t walking by the time they are one year old?

- Should preschoolers know how to cut out shapes with curved lines and use spatial vocabulary terms?

- When do children start to learn empathy, compassion, and self-regulation skills?

- How many words should a child be using if they speak more than one language?

Yes, we want answers…we want to know when a child is on track, of track, when to revise instruction, etc. This desire, has left many of us searching for credible milestone charts, growth charts, learning progressions, and tests that may reveal the answers we seek.

Given my work with young children for the past 25 years, however, and my work in early childhood assessment in particular, I hate to disappoint, but there isn’t a magic wand that will help reveal the answers we seek.

And I certainly don’t have a crystal ball when it comes to answering such complex questions about children’s development and learning.

What I do know is:

- Development and learning is highly variable and this variability only increases with age

- There are numerous factors that impact a child’s development and learning

- Teacher quality, while important, is not the biggest predictor of development and learning

- Using age-equivalencies lead to greater misinterpretations than accurate interpretations

- Many of the tools early educators have access to with “age markers” have not been sufficiently researched for use in making high-stakes decisions

So where does that leave us? What can we do to begin to answer these important questions and make decisions about children’s development and learning?

Here are my recommendations…

First, begin to answer any question about a child’s development and learning, using an authentic assessment approach. Meaning, ensure that familiar people gather information, in familiar settings, and use familiar toys and objects.

Second, avoid relaying on age-equivalencies, especially those with face validity. Rather, consider all the factors that impact a child’s development and learning when making high-stakes decisions.

Third, use charts, progressions, and tests where scores and interpretations are known to be valid and reliable for the population of children you serve and for the answers you seek.

A tall order I know; however, these practices are the only way in which we can put trust in the decisions we make.

So while I don’t have a crystal ball, I do have a few ideas on how you can begin to answer pressing questions about children’s development and learning.

To get you started…Here are a few of my “go to” resources when I want to better understand developmental expectations and/or learning progressions.

Assessment, Evaluation, and Programming System for Infants and Young Children (AEPS), Second Edition, by Bricker et al., 2002

(Contact me if you would like training on the AEPS.)

The AEPS is a highly respected curriculum-based assessment system that is used to accurately assess children’s current skill levels, target instruction, monitor child progress, and aid in identifying disability and determining eligibility. (Description taken directly from the AEPS Linked System website).

While you can administer, score, and interpret the AEPS, you can also just use it as a reference. Meaning, as a good source to improve your knowledge of child development.

For example, inside the system, you’ll find small “hierarchies” of skills. The image to the left contains a hierarchy for “interacting with objects”.

The hierarchy begins at the bottom (like the bottom rung of a ladder) and makes its way up to the top, which is the “highest” form of the skill in an age range. This particular example is from the Birth to Three portion of the AEPS.

I use this hierarchy to help me understand what the typical sequence is for many children as they learn through interacting with objects. I also use the hierarchy to understand how best to support children who may be struggling.

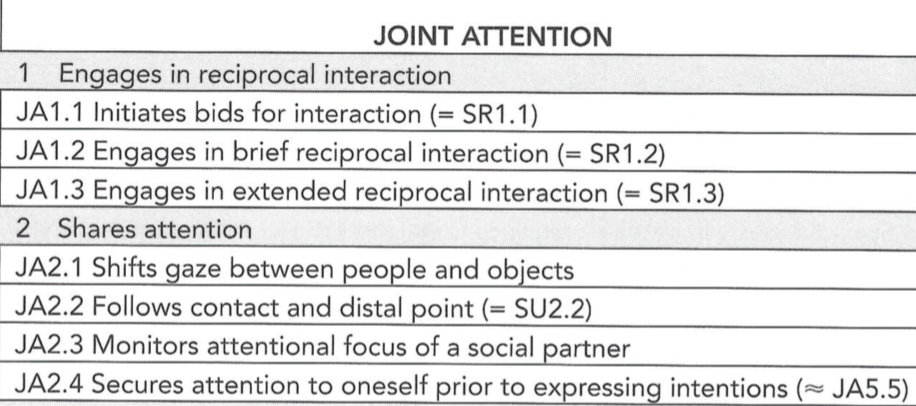

The SCERTS® Model: A Comprehensive Educational Approach for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders developed by Prizant, Wetherby, Ruibin, Laurent & Rydell 2005

The SCERTS® Model is a research-based educational approach and multidisciplinary framework that directly addresses the core challenges faced by children and persons with ASD and related disabilities, and their families. SCERTS® focuses on building competence in Social Communication, Emotional Regulation and Transactional Support as the highest priorities that must be addressed in any program, and is applicable for individuals with a wide range of abilities and ages across home, school and community settings. (Description taken directly from the SCERTS website).

Again, while teams can administer, score, and interpret the SCERTS, I use it to help me understand the progression of critical skills, such as joint attention.

Within the system, the progressions are clustered across three levels: social partner, language partner, and communicative partner. Within the levels, each skill is operationally defined and placed in a progression from earliest/easiest (1.1) to later/harder (2.4).

Free website by Clements and colleagues (do need to set up a fake classroom, but don’t need to enter any child data) with learning trajectories for early math skills

Includes alignment for trajectories with TS Gold Objectives

More Learning Trajectories for Primary Grades Mathematics by Clements and colleagues

This document provides a description of the developmental progression that children follow as they learn a mathematical concept/goal (i.e., counting, adding, measuring, multiplying, composing geometric shapes, etc.).

This document provides a description of the developmental progression that children follow as they learn a mathematical concept/goal (i.e., counting, adding, measuring, multiplying, composing geometric shapes, etc.).

Each concept is defined, described and broken down into recognizable stages.

• Math in the early years [pdf]

• Technology-enhanced, Research-based, Instruction, Assessment, and professional Development [link]

• NAEYC article [pdf]

Here are a few other trustworthy sources regarding developmental and learning milestones:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Milestones in Action

- North Carolina Early Learning and Development Progressions: Birth to Five

- University of Michigan Health System

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association

- Milestones and Tips from Zero to Three

- Center on the Developing Child Harvard University

- Erikson Early Math Collaborative

I also encourage you to become a member of the Division for Early Childhood and/or the National Association for the Education of Young Children. Both of these professional organization can help identify credible sources and resources to guide your work with young children.

References for go to resources:

- Bricker, D. D., Capt, B., Pretti-Frontczak, K., Johnson, J., Slentz, K., Straka, E., & Waddell, M. (2002). The Assessment, Evaluation and Programming System for Infants and Young Children: Vol.2 AEPS Items for Birth to Three Years and Three to Six Years (2nd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- McClelland, M. M. & Tominey, S. L. (2015 ). Stop, Think, Act: Integrating Self-Regulation in the Early Childhood Classroom. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Prizant, B. M., Wetherby A.M., Rubin E., Laurent, A. C., & Rydell, P. J. (2006). The SCERTS MODEL: A comprehensive educational approach for children with autism spectrum disorders. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

P.S. Here is a rubric we created related to learning to write. Hopefully it illustrates how we can look more wholistically at development and learning.